- July 8, 2025

Last weekend I was listening to a podcast where the host was interviewing an investment manager from a large Wall Street investment firm. The manager was touting the success of his pre-2020 prediction that there would be a “correction in excess of 10%” during 2020 that would provide a good opportunity to “add risk to their portfolio.” He did admit that he was wrong about the cause and magnitude of the correction, though.

Underlying his not-so-bold prediction are a few valid points for discussion. Stock prices do decline or correct periodically, and the decline is rarely caused by expected events. As such, it’s helpful to have a plan for the unexpected events that will inevitably arise, before they happen.

Here are three related investment questions you might be wondering given the unexpected and expected events of 2020. Be sure to read (or skip) to the end for the bonus question.

Are we due for a pullback?

“It seems like stock prices have risen too far, too fast.”

“How can stock prices have risen so high when there is still so much uncertainty in the economy?”

“Stock prices must be due for a correction.”

These are statements and questions that have been commonplace in recent weeks. There are dozens of valid reasons why stock prices have risen as much as they have. And there are also dozens of reasons why they might be due for a pullback. There are similarly valid quantitative reasons that stocks are over-valued, as there are reasons they are appropriately valued.

This constant tug-of-war is what causes stocks to rise or fall in any given day – sometimes more and sometimes less. Imagine a real-life game of tug-of-war where the long-term average Price to Earnings ratio on stocks is the center line. Some days one side of the rope gets pulled harder when risks are most heavily weighed by the market. Some days the other side of the rope is pulled harder when the positives are most heavily weighed.

Only one reason for a brief decline in stock prices, though, is universally true and almost never cited. Stocks simply do not rise uninterrupted forever. In any given year we can expect stocks to experience a decline of roughly 10% to 14%, even in years that end with positive returns. The reason for a decline is nearly always something that was not foreseen ahead of time, was random, and therefore unpredictable.

Of course, the decline we experienced in 2020 was far greater than 14%. However, it was caused by what may very well be the most random reason imaginable, a global pandemic. When risks of the worst-case scenarios subsided, stock prices responded by rising.

Stocks of companies that actually benefited from 2020’s predicament have risen the most. These rebounders have been some of the largest companies in the S&P 500 index. Because of this, their rise has hidden the many corners of the market that have not been so fortunate.

As we get closer to 2021, it is natural to ask or wonder if stocks will take a break from their historic run since the end of March and experience a decline or correction. Statistically, yes, the odds favor that happening. But that is not a reason to change one’s investment plan.

We cannot know if a potential decline will be 5% or 35%, when it might occur, or what will cause it. And basing a plan on the next stock decline is not a plan, but rather a reaction. A thoughtful investment plan will help you be successful whenever the next decline happens, how deep it is, and regardless of its cause.

Are Apple and Amazon going to become the entire market? Are they going to crash and take down the entire market?

Right now it seems like Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and other large technology stocks can do no wrong and should be the best place to invest for a technology driven future. It also seems plausible that their rapid ascent could reverse and have negative ripple effects on the overall stock market.

Let’s take a look at what the data and history tell us about the largest stocks in the S&P 500.

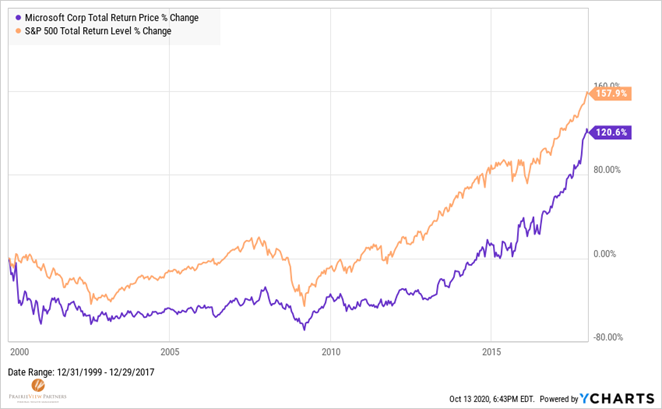

Microsoft was the largest stock in the index in 2000, at about 5% of the index. This during a time when technology stocks were driving the index’s gains, not unlike today. Microsoft’s return trailed the index for the next 18 years.

During that time, it remained a leader in its market, grew its earnings and market share, but also had a few product missteps. It rose too far, too fast, and it took 18 years for results to catch up to expectations despite remaining a great company.

ExxonMobil was the largest company in the index in 2007. At that time the price of oil was rising and the world couldn’t get enough of it. The best-selling smartphone was the Blackberry and Amazon was losing money hand over fist. Alternative forms of energy were seen as fringe and uneconomical. It would still be five years before Tesla released the Model S.

Since the end of 2007, Exxon has lost 44% including dividends, has been removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average and has a lower market value than the world’s largest provider of wind and solar energy, NextEra Energy.

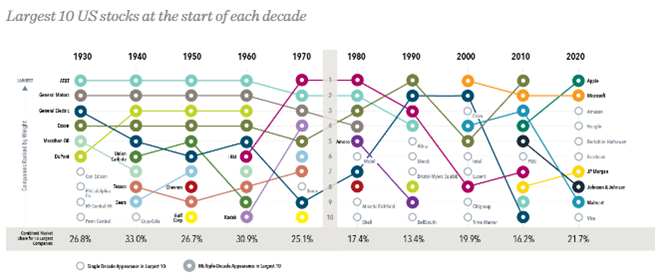

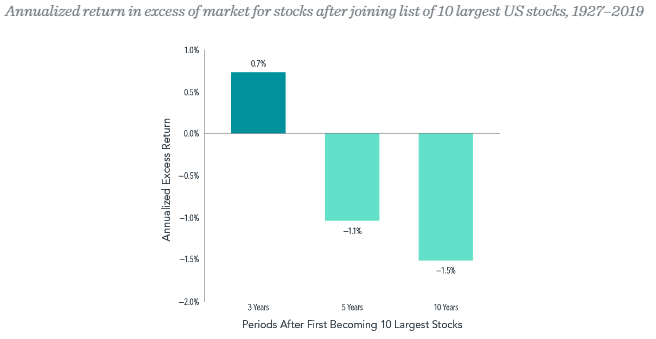

Those are only two examples but there are many more. When we look at the total of those “many more,” we see that after a company becomes the largest in the index, its prospective returns suffer. This is because, as in the case with Microsoft, so much of its future performance is reflected in the share price at the time when it is one of the largest companies in the index.

Other notable examples include AT&T, IBM, and General Motors. There was a time when the phrase of the day was “as goes GM, so goes the US economy.” At one point, IBM was effectively the entire technology sector.

After a company has become one of the 10 largest in the index, its annual return for the subsequent ten years on average has been -1.5% per year. Often it has been a situation like Microsoft where the valuation ran ahead of the results, but sometimes it is the result of new innovation leaving an old company behind, as in Exxon. Unfortunately, there is also the case of GE, where much of the downfall stemmed from mismanagement. Regardless the scenario, other companies took the lead and the index prospered.

Also, it’s important to remember that despite its popularity, the S&P 500 is not the entire investable market for stocks. In a diversified portfolio, if the largest companies take a break from continued share price growth there are Small Cap Stocks, International Stocks, and those often-forgotten Value Stocks that also contribute to long-term returns.

The Elephant and the Donkey in the room – how will the presidential election affect the market?

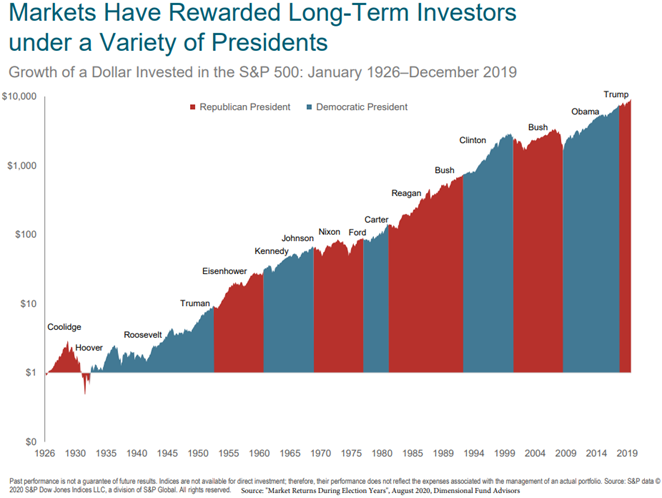

By now we’re all aware that there is a Presidential election this year. In fact, it will only be few weeks after you might be reading this. Without providing commentary on this (or any) specific election, every election is important in a free society. Unfortunately, they tend to be emotionally and ideologically charged events, and they tend to bring out the worst of the economic and investment prediction machine. These are precisely the reasons why, in the words of Warren Buffett, “it’s a mistake to mix investing and politics.”

Despite polling and related speculation, there is no way of knowing who will win, what direction congress will go, what policies will be enacted, what will happen that is beyond politicians’ control, or how financial markets might respond to any of these outcomes.

If that sounds like a difficult environment in which to be making investment decisions, it’s because it is. That’s why it’s as important a time as ever for your investments to reflect your plan rather than external factors.

It’s easy to believe that the President of whatever party we prefer will be most beneficial to stock returns or that the other party’s candidate will present too much risk. The truth is that stock returns have been quite good regardless of the President. Stocks represent companies that operate every day to serve their customers and shareholders, and their success in achieving those objectives is what will propel their prices and dividends higher.

Bonus Question: Should we do anything with our investments before a market decline, tech stock crash (or continued rally), or Presidential outcome?

This question is best answered with another question. If you change your investments ahead of any anticipated event, is it a permanent change or a temporary change?

If the answer is a permanent change, then let’s be sure it aligns with your financial plan and needs.

If it’s a temporary change, then it becomes a reaction to an external factor that likely has nothing to do with your plan. Further questioning is required:

- If you sell stocks before the event in question happens, will you be able to buy them back if they fall after the event? What if they rise after the event?

- If you sell stocks before the event in question happens and it doesn’t actually happen, will you keep waiting for it to happen or will you be able to return to your planned investments?

- If you buy more stocks before the event in question happens and stocks decline, will you throw in the towel or will you take the long-term view?

I could go on, but by now you probably know where I’m going with this. Not only do we not know exactly what might happen or when, but it’s exponentially more difficult to predict how financial markets might respond to an event.

The risks associated with investing throughout or in the face of uncertain events are what allow for the gains stocks have provided over the years. The amount of risk you take with your investments should reflect your needs and not the external factors that are outside of your control.

Matt Weier, CFA, CFP®

Partner

Director of Investments

Chartered Financial Analyst

Certified Financial Planner®